Sinking of troopship Windsor Castle

By H A B White

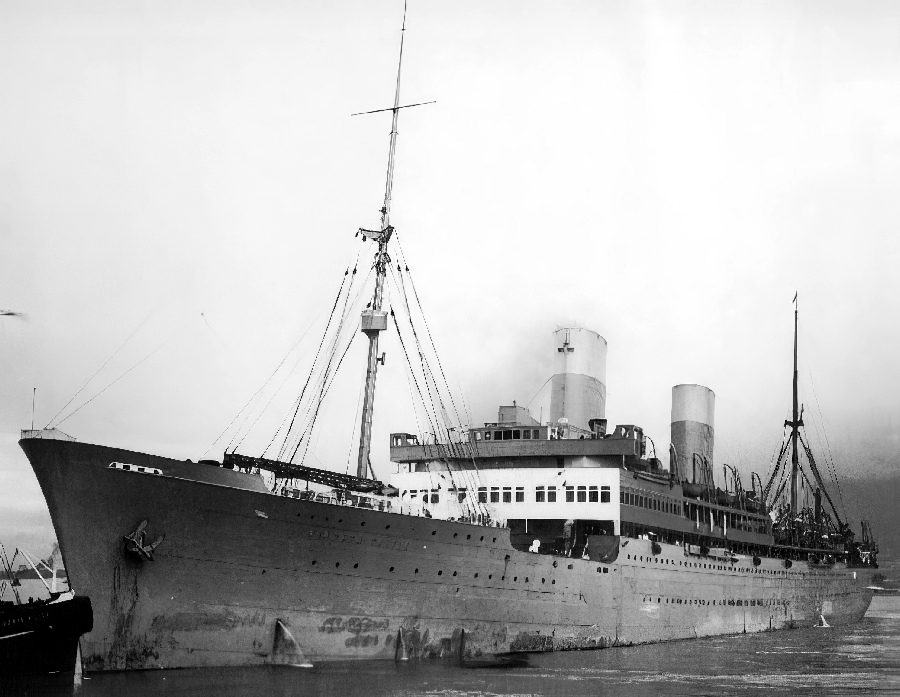

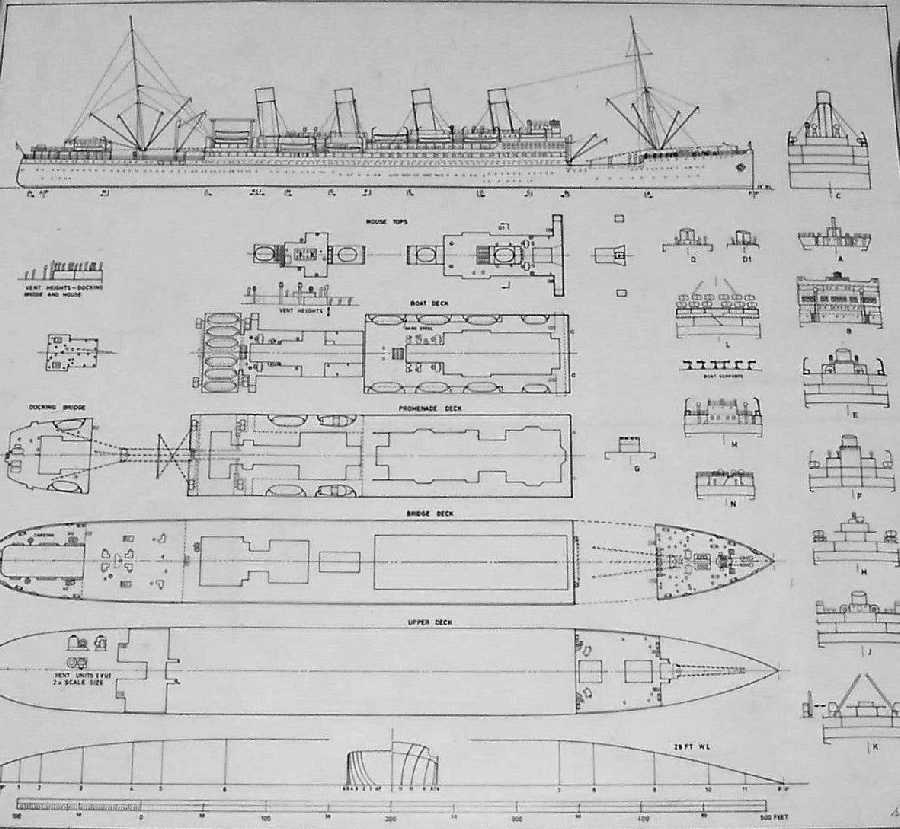

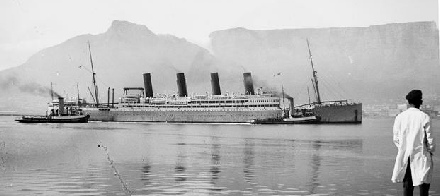

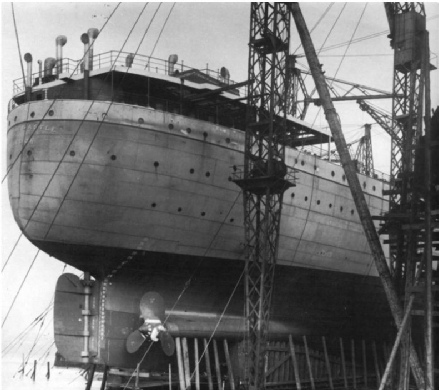

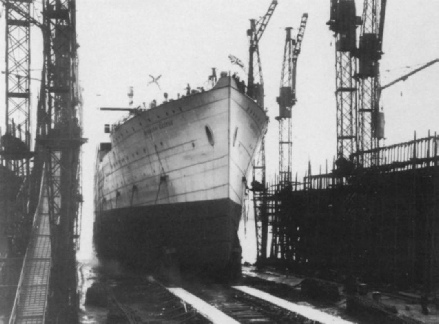

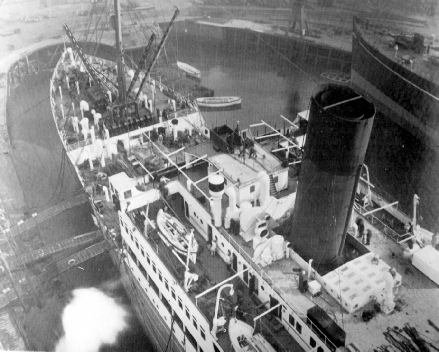

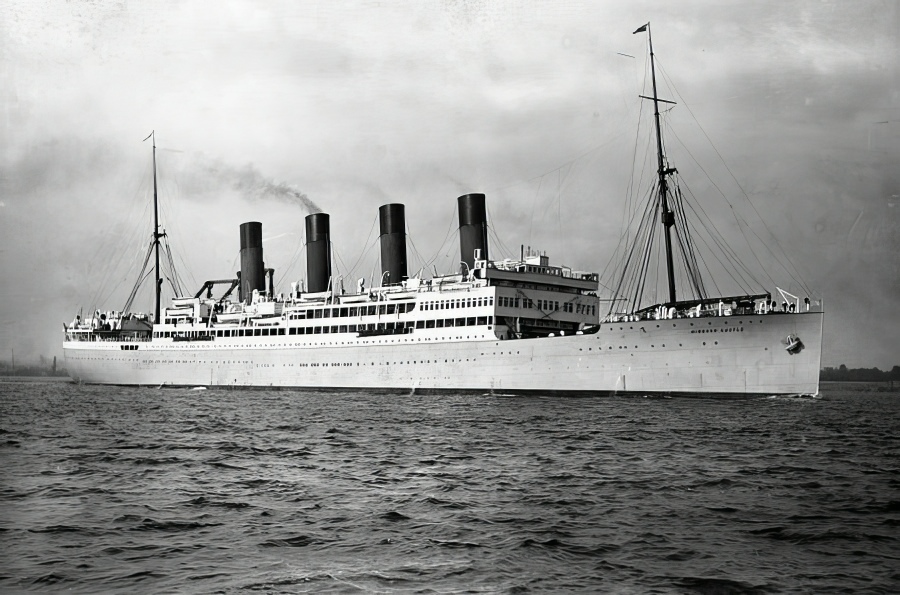

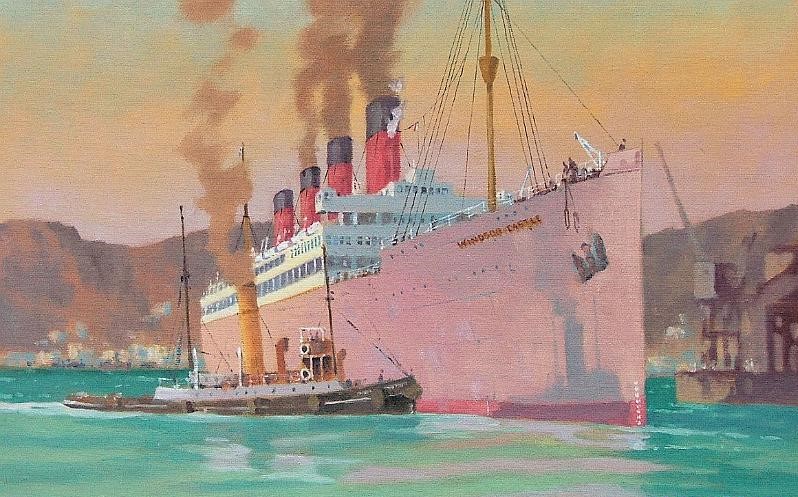

In mid March 1943, the troopship Windsor Castle", once luxury liner of the Union Castle Line, slipped down the Clyde to join convoy KMF 11. Over 2,500 men were packed on board.

When the ship began to heave, side-slip and wallow in the Bay of Biscay, we on "E" deck, the lowest habitable quarters for troops, dripping with sweat, some sea-sick, would compete for the small air vents fixed in the deck roof. Fortunately we were not confined below decks all the time, but would come up for PE and boat drill. Soon we could find our rafts stations with the minimum of disorder.

None on E deck saw the Rock of Gibraltar because we had been ordered below. We then knew that our destination was North Africa and we spent the earlier part of the night packing our kit ready for disembarkation. After that we lay back in our hammocks, slung over the mess tables, some of us contravening orders to spend the whole voyage fully clothed.

The atmosphere was sweltering. Some removed boots, others jackets and a few undressed completely.

Towards midnight "E" deck grew quiet. I lay in my hammock trying to read Oscar Wilde's "De Profundis" , until the heat made even reading an effort. My boots came off. I loosened my battledress jacket and dozed off.

A jarring thud shook me awake. I had leapt from my hammock and was groping for my boots before even thinking what I was doing or what had happened. The throbbing of the engines had suddenly stopped. The lights had gone out. Men were dropping to the floor searching for boots and life belts. Now there was shouting. Panic was beginning to gain hold when a belated bell sounded in the darkness. It suddenly stopped. There was complete silence for a second or more before a reassuring voice was raised. I cannot remember what it said, but immediately the feverish rush towards the stairs leading up to "D" deck became more orderly.

We climbed up to "D" deck and paddled through a swirl of ankle-deep water to the stairway leading up to "C" deck.

The air was reeking of cordite and I realised that we had been torpedoed and wrongly believed that the ship was sinking rapidly. It was almost pitch dark and there was a hole where an iron hatch cover of the hold had been torn off. by the force of the explosion.

Our instructions had been well practised and were quite plain. We made our way to our emergency raft stations amidships on the port side. As we approached the rails to take up this position we could see silhouetted the shape of a lifeboat swinging vertically towards the sea held by a single rope. We strained our eyes in the darkness. There was only one other lifeboat visible on our side. The others must have been lowered as we were climbing up from "E" deck.

I passed Waring on the way and asked if he had seen Dick Burrow, but he was shaken and did not reply. Then I reached the raft station where a man on my left had fainted and room had to be made for him. Behind me came a soft staccato rattling. Simmond's teeth were chattering and he kept asking whether we would be saved.

A roll call was taken but was not complete because so many men were milling about on deck that movement was slow.

We could see flashes of morse signalling at sea now and our ship's relay system was giving orders, but we could not hear it distinctly. The words sounded like "Prepare to abandon ship quietly".

Our RSM (Regimental Sergeant Major) ordered us to remove our boots and stand ready to lower the rafts, so those wearing boots took them off and tied them round their necks. Others shuffled around in stockinged or bare feet.

We stood thus for about half an hour, Simmonds asking questions, trying to convince himself that we could not drown.

Crew members lowered the last remaining lifeboat on our side, shouting and giving instructions to each other in the gradually lessening darkness.

There was bitter moaning in our ranks as this boat left, but the RSM tried to maintain silence, in case a U boat was lurking near. He told the sergeants to take he name of the next man who spoke. This order aroused only jeers.

It was now nearly 4 a.m. by the luminous dial of my watch. I took it off my wrist and transferred it to my battle dress top pocket. More signalling. More waiting.

The flashes from a ship in the distance seemed to be coming slightly nearer. I began to wonder how long our ship would stay afloat and how many men a rescue ship could take off. Would there be a wild dash towards it? Would there be more than one ship? Such thoughts ran through my mind, filled more with heavy anxiety than with stark fear.

At long last the outlines of a destroyer appeared. It swept alongside. There were shouts of "Keep back! Keep back!" as the crowd surged towards it. The ship passed us by and, as we were to learn later, made a circuit of our troopship, coming to rest on the starboard quarter. We had moved further down the deck and could now see hoards filling the destroyer right up to its funnel. Obviously there would be no room for us.

We moved back to our original stations. After another long wait the loudspeaker on board announced that a second destroyer would be coming to take us off. In the now growing light we saw it racing up, to station itself on our port beam . We started to form an orderly queue and I grabbed one of the blankets which had formed someone's bed prior to the torpedoing.

To board the destroyer, the Whaddon, we had to climb on to the liner's rail, about five feet high, surrounding "C" deck, lean out to grasp a rope hanging down the side on which the lifeboats had been lowered and slide down some 12 feet on to the destroyer's deck.

Willing hands from the destroyer's crew anchored the rope and held it out at an angle between liner and destroyer.

When my turn came, I gripped the rope, coiled my legs round it and slipped down in the orthodox manner, hand under hand , slewing a little at the end, landing without harm. The sense of relief was tremendous.

They swarmed down the ropes, all shapes and sizes of men, without jackets, boots, even trousers, some afraid to slide down and hanging back, others slipping out of control in their hurry to leave, chafing the skin off their hands. It was no easy matter to take the strain on a rope that had to be held out at an angle of about 20 degrees from the vertical and to support on it a man's weight, as I found when taking a turn on the destroyer's deck.

One man, a rope away from the one I was holding out, fell into the sea but was pulled out later, we were told.

Our destroyer took about 1,000 men on board and the captain warned us over the microphone to stand well inboard. There was indeed little space. I found a position up beside the hot funnel The captain also explained that we should have to remain close to the liner until a third destroyer arrived to guard it. Meantime a flying boat and a fighter would be coming up to protect us. He had barely finished speaking when the call "Action Stations" came over the destroyer's loudspeaker and its pom-poms started firing. This was a false alarm, heralding the arrival of our air escort.

It was early dawn when we began to cruise slowly round the Windsor Castle at a distance of about 200 yards. For the first time it was possible to gain some overall idea what had happened. We could see several lifeboats and rafts dipping aimlessly into the waves. From several came pinpoint torch lights, from others we could hear voices calling to us. The microphone of our destroyer answered the men in the boats and clinging to the rafts , "You will not be left behind. Another destroyer will pick you up. You will not be left behind."

I counted seven lifeboats. Two of these were waterlogged and empty. There were also many rafts. I could not understand why so many men were in the water, since we had received no orders to jump into the sea, merely to be ready to do so. As life belts, rafts, wood, boxes, other flotsam and patches of oil floated by, I realised that many had in fact carried out an order intended as preliminary advice only.

Later on the Whaddon also started to pick up more survivors, including some from our unit. There was a burial at sea. We were told that this was for a REME (Mechanical Engineers) sergeant who had been picked up dead. One of the engine room men on the liner had also been killed. We never discovered how many men who took to the lifeboats, rafts, or jumped into the sea were lost.

Shortly after 6.45 a.m., the third destroyer arrived and took over the guarding of the liner which seemed to be sinking stern first, judging from the water line which was no longer visible in that quarter.

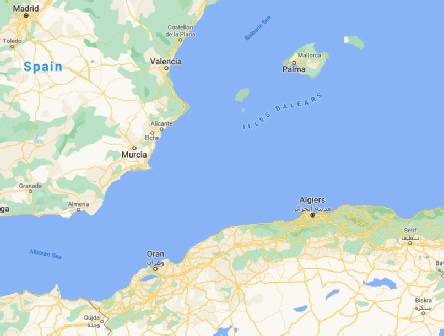

We drew clear of the wreckage and gathered speed for Algiers, landing there safely.

Postscript.

Although we received official notice that all our kit had been lost, I decided, years later, to write to Lloyds of London for confirmation of the sinking. The reply was laconic " By 17.25 hours the vessel was completely submerged,"

The Windsor Castle now lies on the ocean bed some 60 miles NW of Algiers.

Report from the Admiralty.

"At 0202 on March 23rd, K.M.F.11 was attacked by torpedo aircraft in 37.28 N., 01.10 E., about 60 miles W.N.W. of Algiers. The WINDSOR CASTLE, 19,141 tons, carrying 2,500 troops, was torpedoed.”

The DOUGLAS, WHADDON and EGGESFORD stood by, but the ship sank at 1120. Only one life was lost.

Captain J.C. Brown, R.N.R. Master of the WINDSOR CASTLE, stated later: “The torpedo struck us fair and square. The engine-room was flooded, but the entire engine-room crew, with the exception of one man, were washed through the bulkhead door to safety by the inrush of water. I did not see a sign of panic. Over 2,000 British troops waited patiently for the rafts to be cut away. Although the ship was sinking they stood there like troops on parade until finally the destroyers came alongside and took them off".

The times of sinking differ in these two accounts.

This account was written by H A B White and is part of a series of his war time exploits published on the BBC web site under WW2 People’s War

Crew List

Crew List